A new paper from the Transmissible Cancer Group at the University of Cambridge Department of Veterinary Medicine reveals how a transmissible cancer has spread through the Tasmanian devil population, and how this cancer’s genome has evolved and diversified during it evolution.

A young Tasmanian devil. Tasmanian devils are endangered by devil facial tumour 1 (DFT1), a transmissible cancer. Photo credit: Maximilian Stammnitz (CC-BY)

Tasmanian devil facial tumour 1 (DFT1) is a transmissible cancer threatening Tasmanian devils, marsupial carnivores endemic to the Australian island of Tasmania. DFT1 is one of the few known directly contagious transmissible cancers in nature: it spreads between animals by the transfer of living cancer cells by biting. The disease causes horrifying facial tumours and is usually fatal. First observed in 1996, DFT1 has caused rapid declines in the Tasmanian devil population.

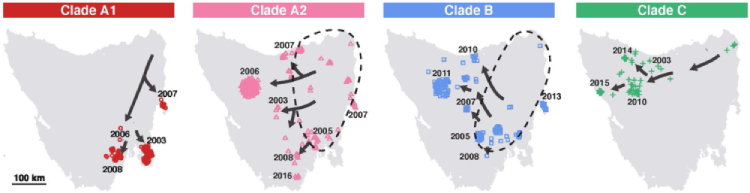

The new research, published in PLOS Biology, annotates genetic changes that have occurred in 648 DFT1 tumours collected from devils throughout Tasmania between 2003 and 2018. These mutations are largely irreversible and can be used as “tags”, which the researchers used to trace the geographical spread of the cancer. This revealed that DFT1 split early into five groups, only three of which have continued to survive. The patterns of DFT1 spread are consistent with epidemiological evidence suggesting that the DFT1 cancer first arose from the cells of a devil that lived in Tasmania’s north-east before quickly colonising areas of central and eastern Tasmania. The new research tracks the cancer’s more recent routes out of this region, and traces the movements of diseased devils over twenty years.

FIG 2

The spread of the Tasmanian devil transmissible cancer known as devil facial tumour 1 (DFT1) across Tasmania. DFT1 has split into five clades; three of these clades and two subclades, named A1, A2, B and C, continue to persist today. Maps show the geographical movements of these clades inferred from their genetics. The dates at which tumour clades were first observed in various sampled populations are labelled. Credit: Kwon et al, PLOS Biology, 2020.

Beyond their use as “tags”, the mutations in the DFT1 genome provide insight into the molecular and evolutionary processes that cause and alter the frequencies of mutations. The researchers found that some mutations occurred repeatedly, suggesting that their presence may provide an advantage to the cancer. One particularly complex series of genetic alterations was observed almost every time DFT1 cells were extracted from devils and grown in a laboratory dish, suggesting that laboratory conditions strongly favour these mutations’ presence. Overall, however, the researchers were surprised by how few mutations were found in DFT1. Indeed, more mutations frequently distinguish two tumours derived from the same cancer within a single human patient than were found between pairs of DFT1 tumours sampled hundreds of kilometres and more than a decade apart.

“DFT1 has acquired relatively few mutations during its thirty-year history,” said Prof Elizabeth Murchison, who led the study. “This research illustrates how a comparatively simple and stable cancer can colonise diverse niches and devastate a species.”

Citation: Kwon YM, Gori K, Park N, Potts N, Swift K, Wang J, et al. (2020) Evolution and lineage dynamics of a transmissible cancer in Tasmanian devils. PLoS Biol 18(11): e3000926. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000926

Contact: Professor Elizabeth Murchison, epm27@cam.ac.uk