Disease recognition by owners & veterinarians

Clinical sings that brachycephalic dog owners should recognise...

- Respiratory noise

- Stenosis of the nostrils

- Gastrointestinal signs

- Obstructive sleep apnea / sleep-disordered breathing

- Heat intolerance

- Cyanosis and collapse

Veterinary assessments for BOAS...

All images are copyright of the University of Cambridge or individual contributors, all rights reserved, no reproduction without permission.

Respiratory noise

Dogs with normal upper airway tract breathe quietly. Respiratory noises such as snoring and snorting are indicators of airway obstruction. BOAS-affected dogs may present with different types of noise depending on the location of the obstruction: pharynx, larynx, and/or nasal cavity. Some BOAS-affected dogs may only have respiratory noises when they are excited, playing, exercising, eating/drinking or under stress. A thorough veterinary examination is recommended if the respiratory noise is marked.

Pharyngeal noise

This type of noise, termed 'stertor' is caused by the elongated and thickened soft palate. The caudal tip of a normal length soft palate should barely touch the epiglottis, so that when the dog pants with an open mouth, the airway is open. However, the soft palate in affected dogs is too long and extends into the opening of the airway (larynx).

When the dog pants, extra effort is required to move the soft palate out of the larynx in order to allow air to pass. When the dog breathes through its nose, the increased negative pressure within the upper airway tract during inspiration can trigger vibration of the soft palate and redundant pharyngeal soft tissues - BOAS-affected dogs can be 'awake snorers'.

Laryngeal noise

This type of noise is particularly common in affected pugs. It is called stridor and it is a high-pitched noise, similar to wheezing and different from low-pitched noises like snoring or snorting. Usually this type of noise indicates a narrowed or collapsed larynx. Laryngeal collapse is considered a secondary lesion that may appear as a consequence of leaving primary lesions (e.g., elongated soft palate and narrow nostrils) untreated.

Laryngeal collapse can be temporary and dynamic. During inspiration, the cartilaginous structures are drawn into the tracheal opening. When this phenomenon has happened for an extended period of time, the cartilaginous structures lose rigidity and laryngeal collapse may become permanent.

Nasal / nasopharyngeal noise

This type of noise indicates nasal obstruction, usually caused by stenotic nares, abnormal growth of nasal turbinates (bony or cartilage scrolls in the nose covered by mucosal membranes), and collapse of nasopharynx. In some dogs, a deviated nasal septum may worsen the situation.

The narrowed nasal cavity results in an increase in negative pressure within the airway lumen, which causes soft tissue vibration and noise. This type of noise may be accompanied by nasal flaring, where muscles around the nose contract during nasal breathing. You may also hear a simultaneous, low-pitched and/or high pitched noise.

or it can be a mixed type obstruction, with pharyngeal and nasal noise:

Reverse sneezing

Reverse sneezing is a common event in brachycephalic dogs, the actual causes of the episode are unknown but it is likely to be related to the elongated soft palate that irritates the throat. Episodes of reverse sneezing usually last from a few seconds to one minute. Usually as soon as it passes, the dog breathes normally again. Reverse sneezing rarely needs treatment. Sometimes, after upper airway surgery, reverse sneezing will stop or decrease in frequency. However, for dogs that have turbinectomy surgery, the frequency of episodes might increase until the tissue debris has been cleared out.

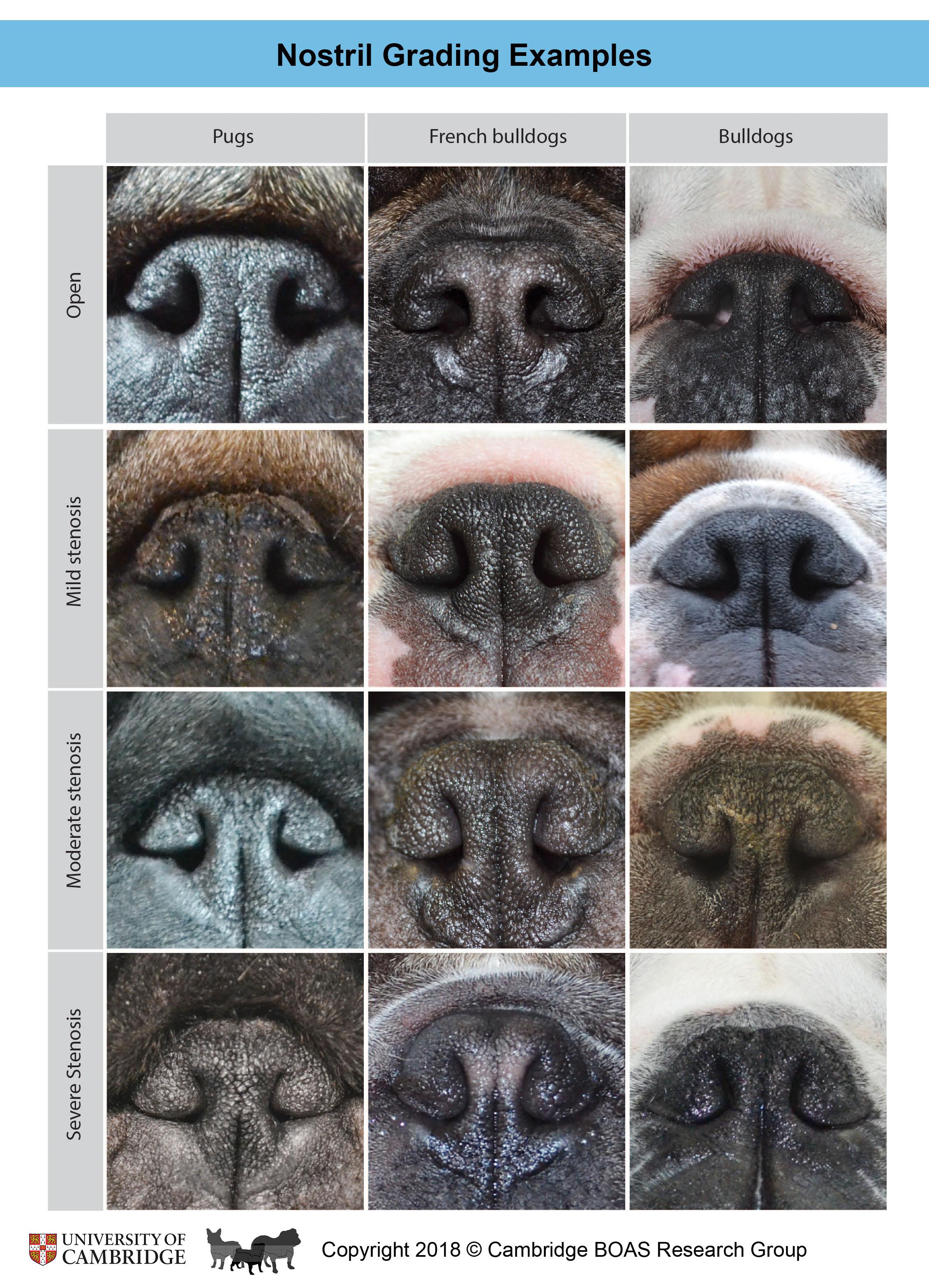

Stenotic nares (narrowed nostrils)

Stenotic nares are excessively narrow and often collapse inward during inspiration, making it difficult for the dog to breathe through the nose properly. Stenosis has been reported not only in the exterior nostrils, but also in the inner part of the nasal wing (nasal vestibule). As a result, respiratory effort and open-mouth breathing are commonly seen in brachycephalic dogs. Stenotic nares are considered a risk factor for BOAS, particularly in French bulldogs. French bulldogs with moderate-severe stenosis of nostrils are about 20 times more likely to develop BOAS (reference). Corrective surgery to widen the nostrils is recommended.

The degrees of nostril stenosis in brachycephalic breeds are defined as follows:

Open nostrils - wide opening.

Mild stenosis - Slight narrowing of the nostrils. When the dog is exercising, the nostril wings move dorso-laterally to open on inspiration.

Moderate stenosis - The dorsal part of the nostril wings touch the nasal septum and the nares are only open at the bottom of the nostrils. When the dog is exercising, the nostril wings are not able to move dorso-laterally and there may be nasal flaring (i.e. muscle contraction around the nose trying to enlarge the nostrils).

Severe stenosis - Nostrils are almost closed. The dog may switch to oral breathing from nasal breathing with very gentle exercise or stress.

Gastrointestinal signs and eating difficulties

Eating difficulties are commonly seen in BOAS-affected dogs. The opening of the oesophagus is located dorsal to the airway opening and behind the soft palate. In BOAS-affected dogs, the excessive pharyngeal folds and the elongated soft palate may impede the swallowing function.

Regurgitation is commonly seen in BOAS-affected dogs. It can be caused by esophageal diverticula (esophageal pouches, a congenital condition) and/or hiatal hernia (stomach partially slides into the chest, it may be a congenital or secondary trait). In BOAS-affected dogs, the chronic increase in thoracic airway pressure draws the stomach into the chest, causing gastroesophageal reflux.

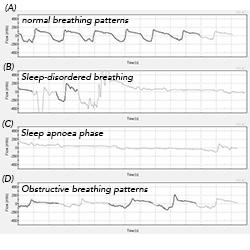

Obstructive sleep apnea and sleep-disordered breathing

Brachycephalic dogs often have a thickened tongue base, a long and/or thickened soft palate, and hypertrophied nasal turbinates, which can obstruct the airway during closed-mouth breathing when the dog is sleeping. Eventually, breathing difficulty (dyspnoea) and periods of no breathing (apnoea) can be observed in these dogs during their sleep. This condition is life-threatening and and affects the dog's quality of life.

Heat intolerance

The canine nasal cavity plays a central role in the dog's ability to regulate its temperature. In order to facilitate heat exchange, a dog's nose is filled with an organized network of thin bone structures that are lined with a highly vascularized mucous membrane. These structures form ducts through which air passes, carrying the released heat away from the body when the dog pants. However, this process is hindered in BOAS-affected dogs that have an obstructed nasal cavity. As a result, BOAS-affected dogs cannot exchange heat as easily as healthy dogs when their body temperature rises during exercise. Because they are not able to cool down, they can suffer from heat stroke, which can lead to organ dysfunction. In addition to an increased body temperature (above 39 C), other symptoms to look for include: excessive panting, excessive drooling, dehydration and rapid heart rate.

(Photo and video to be uploaded)

Cyanosis and collapse

During exercise and sleep, BOAS-affected dogs have great difficulty breathing because of the soft tissue lesions associated with the syndrome. As a result, they may not be able to meet their oxygen requirements. When their blood is inadequately oxygenated, their skin presents a bluish discoloration, which is an obvious sign of cyanosis that can be easily recognized in the dog's tongue and gums. If the dog's oxygen levels are not stabilized immediately, he/she may collapse or become unconscious.

(Photo to be uploaded)

Functional Grading System (clinical assessments pre- and post- exercise)

BOAS clinical signs may not be present at rest in some moderately affected dogs. Therefore, functional grading based on a 3-minute trotting exercise tolerance test is suggested. Instructions on how to perform function grading can be found here: pugs scheme, French bulldog/bulldog scheme. Grade 0 and I are considered clinically unaffected; Grade II and III are considered clinically BOAS-affected and they require management and/or treatment.

Test Result reference:

Grade 0 – BOAS free; annual health check is suggested if the dog is under 2 years old. [Video example]

Grade I – clinically unaffected but with mild respiratory signs, annual health check is suggested if the dog is under 3 years old. [Video example]

Grade II – BOAS affected with moderate respiratory signs. The dog has a clinically relevant disease and requires management, including weight loss and/or surgical intervention. [Video example]

Grade III –BOAS affected with severe respiratory signs. The dog should have a thorough veterinary examination with surgical intervention. [Video example]

Breathing patterns of a bulldog before and after exercise:

Non-invasive respiratory function test

Whole-body barometric plethysmography (WBBP) is a non-invasive respiratory function test that can provide objective information on the dog's airflow. We can use this information to calculate a BOAS Index (0-100%), which can be used to indicate the relative severity of the disease. The procedure takes about 20-30 mins. WBBP is the only non-invasive clinical tool used so far to measure respiratory function objectively. Sedation and anaesthetics are not required. For more information about WBBP...

Diagnostic tests

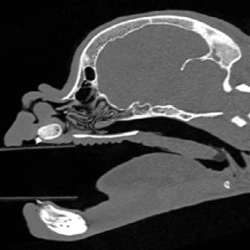

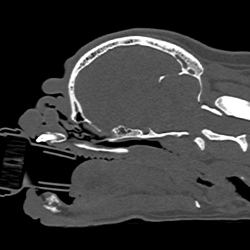

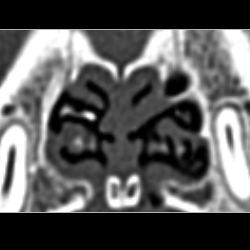

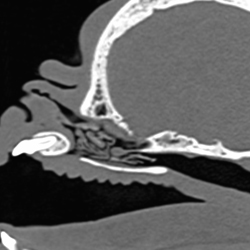

Radiography and CT scans

Head/neck and thoracic radiography or CT scans are part of the diagnostic workup for BOAS. Thoracic radiography/CT scans can assist in the diagnosis of tracheal/bronchial hypoplasia/collapse, esophageal diverticula, hiatal hernia, and aspiration pneumonia. Head/neck CT scans can provide guidance for the planning of surgical techniques such as folded flap palatoplasty, alar fold resection, and turbinectomy.

Soft palate: Elongated soft palate refers to a condition where the soft palate is longer than normal, so that it overlaps with the tip of the epiglottis and extends into the larynx, interfering with respiration. Sometimes the soft palate can be thickened as well. A thickened soft palate can further narrow the pharyngeal and nasopharyngeal area (the airway pathway between the nasal cavity and the oral cavity). CT images are helpful in identifying the thickening of the soft palate and planning the appropriate surgical technique.

Nasal cavity: Canine noses contain a complex network of turbinates—branches of soft tissue that play a crucial role in warming and moistening the incoming air. Brachycephalic dogs often have hypertrophic turbinates that are relatively thicker and less branched. These turbinates are squashed inside the reduced nasal cavity and they can block the air flow in the nose and the nasopharynx. As a result, the respiratory and thermoregulatory function of the nose is greatly reduced. CT scans also allow identification of septal deviation. We can also observe second stenosis of the nostrils, where the inner part of the nostrils collapses (this is not visible from the outside).

Trachea: Hypoplastic trachea is also seen in some brachycephalic breeds, particularly in English bulldogs. The trachea may lose its structural support, making breathing more difficult. It may initiate the development of a chronic cough and respiratory resistance.

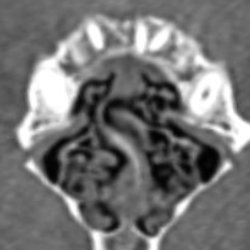

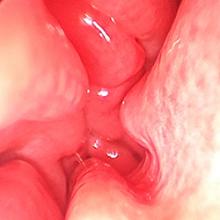

Laryngoscopy and endoscopy

Pharyngeal, laryngeal, and nasal cavity lesions can be assessed via laryngoscopy/endoscopy under sedation or general anesthesia.

Pharynx: soft palate and tonsils

Pharyngeal lesions include elongated and thickened soft palate, enlarged and extruded tonsils, as well as redundant soft tissues and proportionally enlarged tongue.

Larynx: cartilages and saccules

The larynx is a cartilaginous structure controlling the airway opening between the oral cavity and the trachea. The increase in negative pressure within the airway lumen chronically draws the laryngeal soft tissues (saccules) and cartilages into the airway lumen. Eversion of the laryngeal saccules is a condition where the soft tissue located in front of the vocal cords becomes visible, swollen and inflamed. These protruded laryngeal tissues are then pulled into the airway lumen, acquiring the shape of saccules and partially obstructing airflow. In the more severe cases, the cartilage that supports the larynx may also collapse.

Some forms of laryngeal collapse are dynamic, which is commonly seen in pugs: the laryngeal structures and function are relatively normal when the dog is at rest; the cartilages only collapse toward the airway lumen when the dog is exercising or excitable. Some dogs even develop paradoxical breathing, means that the larynx closes on inhalation and opens on exhalation.

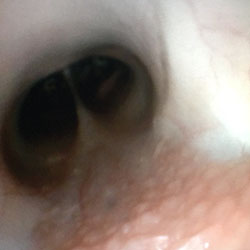

Nasal Cavity

Rhinoscopy is particularly helpful for assessing nasal obstruction, and planning for laser-assisted turbinectomy or radiofrequency ablation turbinate volume reduction. Common lesions in dogs with BOAS include septal deviation, hypertrophic nasal turbinates, and normal growth of the turbinates (rostral aberrant turbinate and caudal aberrant turbinate). The increased mucosal contact points are one of the methods to evaluate nasal congestion.

Rhinoscopy is particularly helpful for assessing nasal obstruction, and planning for laser-assisted turbinectomy or radiofrequency ablation turbinate volume reduction. Common lesions in dogs with BOAS include septal deviation, hypertrophic nasal turbinates, and normal growth of the turbinates (rostral aberrant turbinate and caudal aberrant turbinate). The increased mucosal contact points are one of the methods to evaluate nasal congestion.