Intervertebral disc disease in dogs

Intervertebral disc disease (IVDD) is known to have a lifetime prevalence of ~20% in the Miniature Dachshund, and is fatal in 25% of cases. There is a perception that dogs which are more severely affected require decompressive surgery to recover ambulation, and a small amount of evidence to support this. The severe clinical signs are distressing to owners and further compounded by high financial costs of cross sectional imaging and surgery. It is however known that some dogs will recover without the need for surgery, and in 2017 I carried out an extensive data mining exercise which showed that recovery rates of dogs suffering from thoracoolumbar IVDD treated with medical therapy are similar to those following surgical management in all grades of severity except the most severely affected dogs (Freeman and Jeffery, JSAP 2017: 58, 199-204).

My first PhD student carried out a prospective study of dogs rendered non-ambulatory following suspected acute thoracolumbar IVDD and treated medically rather than surgically; these dogs receive an MRI scan to confirm diagnosis, followed by a second scan after three months of medical management. It is known that in some cases both in human and canine disc herniation the herniated material is removed by natural processes (Argent et al 2019) and we were able to document the frequency with which this occured as well as the recovery rate of these dogs. We were able to convincingly answer our primary question: Can dogs rendered non-ambulatory following acute compressive thoracolumbar intervertebral disc herniation recover ambulation without decompressive surgery? with an emphatic 'Yes', with our recovery rate being as good as that documented for surgical treatment. The answer to our secondary question: Is recovery of ambulation and/or speed of recovery associated with removal of extruded disc material from the vertebral canal? was a fairly convincing 'No', although we documented a significant reduction in spinal cord compression in a majority of affected dogs.

Ultimately we were unable to provide an answer to the key question: In dogs suffering acute severe thoraclumbar IVDD, which cases genuinely require surgical treatment, and which may recover just as well with medical management, since in this cohort at least, almst all recovered with medical management alone.

There are many other unanswered questions surrounding the pathogenesis of intervertebral disc extrusion in dogs as well as humans.

Some of the key questions we have are:

- Why should disc calcification lead to an increased risk of disc extrusion?

- What is the mechanism of disc calcification?

- Can the process of calcification (and therefore disc extrusin) be interrupted or stopped?

- Whet is the true genetic basis of IVDD

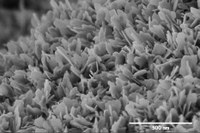

Additional work being carried out currently by my second PhD student with the assistance of Jonathan Powell’s biominerals laboratory, Professor Rachel Oliver from the Dept of Materials Science and Metallurgy and Professor Melinda Duer from the Department of Chemistry (among others) is aimed at characterising the role of calcification in IVDD. We are able to compare the mineral analysis of extruded and non-extruded disc material. Our early results indicate, as expected, a very high level of calcium and phosphorous in extruded disc material removed from the vertebral canal of clinical cases, and we have now been able to establish the nature of this calcified material in both extruded and non-extruded discs. We are now attempting to determine biomechanical features of this material on a micro- and nanoscale using microindentation and atomic force microscopy, as well as elucidating some of the chemical pathways involved.

It has been demonstrated that there is a genetic basis for IVDD in dogs, with the retrogene FGF4 on chromosome 12 being implicated. My latest PhD student is about to begin a project looking into the genetic basis of intervertebral disc disease, in collaboration with Cathryn Mellersh and the Kennel Club Genetics Centre. We have already carried out large breed surveys of the cocker spaniel and French bulldog looking at various lifestyle factors which might play a role in IVDD. We now aim to analyse this data and at the same time begin genetic analysis of affected ad unaffected dogs with the hope of identifiying further genetic tools which may enable selective breeding to reduce the incidence of IVDD.

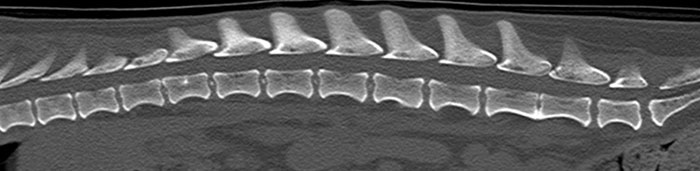

Finally we are involved in a newly launched Kennel Club screening scheme for Dachshunds which provides guidelines for breeding based on the numbers of calcified discs identified by radiography. We are able to offer a CT scan alongside the radiographs, a much more sensitive modality for identification of disc calcification, with the aim of following these dogs and assessing their likelihood of suffering IVDH later in life.

In addition to this work, I am collaborating with bioengineers George Malliaras and Christopher Proctor, who have designed an electrical stimulation device intended to deliver an oscillating electrical field to injured spinal cord, as well as Ben Woodington whose work includes the development of micro-sensors capable of detecting electrical activity from deep within the brain. Thes projects have potential applications in both veterinary and human neurology and neurosurgery.